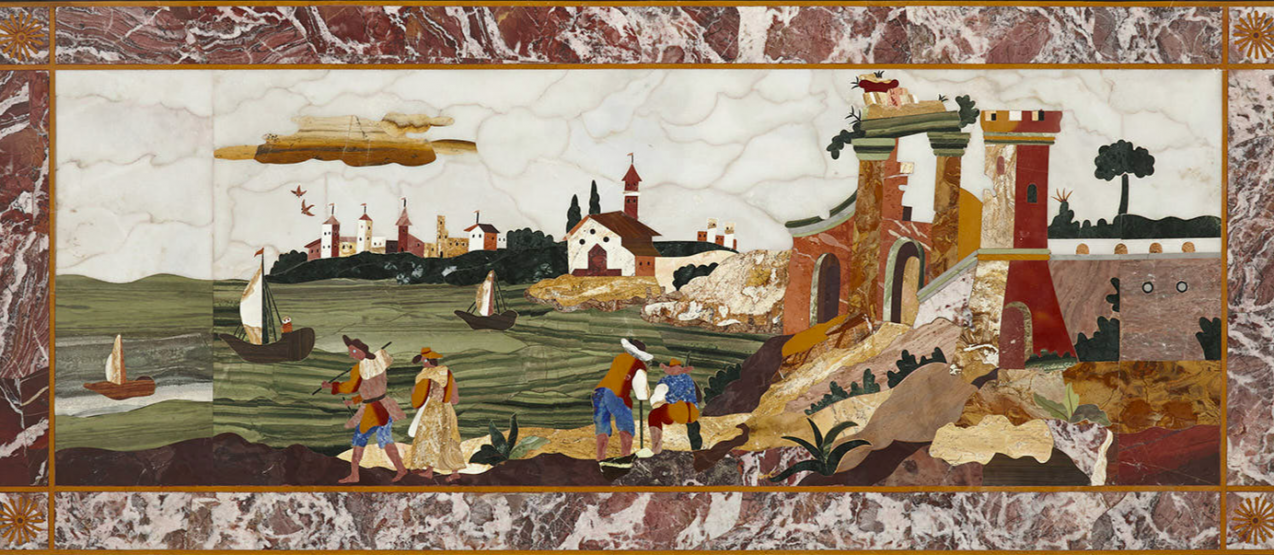

The development of the technique – often called ‘painting in stone’ – was one of the many achievements of the Florentine Renaissance, and it has produced some particularly spectacular pieces.

What makes it so appealing? Like many other forms of antique decorative art, pietra dura is valued for its ability to combine luxurious materials in novel ways. It is a notoriously difficult skill to do well and lies somewhere between the arts of sculpture, inlay, and mosaic. The best pietra dura artists from history have had to demonstrate a virtuosic mastery of all three crafts.

What is pietra dura?

Pietra dura is an Italian phrase, and literally means ‘hard stone’. It is sometimes referred to by the plural pietre dure, or ‘hard stones’, and very occasionally it’s known in English as ‘Florentine mosaic’. It refers, however, to a technique of inlaying differently-shaped and coloured stones onto a backing. In India – another place where the technique was popular, as we will see – the technique is known as parchin kari. Confusingly, in Italy the technique is also called commesso, meaning ‘fitted together’: the ‘pietre dure’ simply refer to the stones used in the technique.

The technique and effect of pietra dura is similar to that of marquetry in woodwork: they are both inlay techniques. Where marquetry involves the inlay of cut pieces of wood and other materials onto a veneer, pietra dura involves the inlay of stones. As well as marquetry, pietra dura has been compared to sculpture, in the sense of it being a method of cutting stones; and as a form of lapidary work, pietra dura can also be considered part of the jeweller’s craft.

Additionally, in the sense of being a method of inlaying stone tiles, pietra dura is also similar to the older technique of mosaic. It differs, however, from mosaic-work in that, while mosaic tiles are roughly the same size and shape – and the image emerges through the arrangement of different coloured tiles – in pietra dura the tiles are cut according to which part of the image they make up.

Common images in antique pietra dura work include patterns of flowers and fruit, Renaissance-style comedia dell’arte figures, and very occasionally pietra dura is used to replicate paintings and icons.

The stones used in pietra dura work have to be hard – in technical language they have to be between the 6th and the 10th degrees of the Mohs scale – so that they can be cut without breaking. Commonly used stones are different types of coloured marble, as well as semi-precious gemstones like quartz, chalcedony, agate, jasper and porphyry; and even occasionally precious stones such as emerald, ruby and sapphire.

How is pietra dura made?

The basic principle of pietra dura is to arrange cut stones into a pattern in such a way that the joins between them are invisible and the resultant pattern appears two dimensional. The major steps involved are as follows:

First, pattern will be designed and then traced. The coloured stones are cut into varying shapes, according to the design, of roughly the same thickness. Cutting would have traditionally been done with an iron wire, used in combination with a variety of different abrasive pastes, to keep the edges of the stones smooth.

The design will then be cut out of the backing stone. The majority of pietra dura work uses black Belgian marble as the backing stone. The coloured stones are then inserted into the spaces where the design has been cut out.

Once the stones have been inlaid, they will be glued in and any gaps filled with gesso to strengthen the back of the panel. The completed plaque will then be polished with abrasive stones and waxed in order to smooth out the surface of the piece.

Pietra dura panels are normally flat, though there are occasions when they are arranged in a kind of low relief: often this kind of stone work is seen on furniture.

The real skill in pietra dura work is in choosing, cutting and inlaying the stones. The joins between the stones have to be practically invisible: this can be done by cutting the mosaic pieces at an angle, so that they fit together like a kind of jigsaw.

In more impressive pieces, the maker will choose and arrange the stones in such a way that their veining will create naturalistic details, such as shadows and tonal variation. This is where the art of pietra dura most closely approaches painting.

Where did pieta dura originate?

Decorative inlays made from stones first appeared in Ancient Rome, with the art form known as opus sectile. This involved inlaying a pattern of stones – as well as other materials such as mother of pearl and glass – into the floors and walls of a building. This tradition continued throughout the Byzantine Empire in the Middle Ages, and was once again revived in Rome in the 16th Century. Because opus sectile was used for architectural features more than for decorative pieces, and because it uses materials other than hardstones, it is considered a separate art form to modern pietra dura.

It was when the craftsmen of 16th Century Florence began to revive these Ancient Roman art forms, and to adapt them to their own tastes, that what we now think of as pietra dura was born. It was indeed the Florentines who first thought of the art form not as a form of decoration, but as a form of ‘painting in stone’.

Pietra dura in Italy

The major impetus for the development of pietra dura in Italy was the ruling Medici family. The Medicis were one of the most powerful merchant families of the Italian Renaissance, and the most prolific patrons of the arts. It was in 1588 that the Grand Duke Ferdinando I de Medici founded the Galleria dei Layori, perhaps the first workshop in Europe to specialise in hardstone carving. He hoped that the new workshop would be able to decorate his residences with opus sectile hardstone work like the Roman palaces of antiquity. It was in this workshop that the first pietra dura objects began to be produced. Expanding beyond the remit of architectural features, the craftsmen at the Galleria started to build caskets, table tops and even cabinets. All of these were used to furnish the vast Medici palaces.

As the art developed across the 16th Century in Florence, it was known as opera di commessi (literally, ‘fitted together works’), where the modern Italian name commesso comes from. These early pietra dura pieces were expensive: stones like jasper, porphyry, quartz and agate had to be mined and shipped from remote corners of the world before being assembled in a commesso panel. It was because of this exoticism and luxuriousness – combined with the technical expertise needed to complete such work – that pietra dura soon became highly desirable among Europe’s most important collectors.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of the Florentine workshop was the decorations in the room known as the Tribuna in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, formerly the Medici’s administrative centre. The workshop in Florence which built the pietra dura elements for the Uffizi and other palazzos in the city would continue to operate, amazingly, until the 1920s. Their pietra dura work would become especially popular collectors’ items for Grand Tourists in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Pietra dura in India

From the 16th Century onwards knowledge of the technique also spread out from Florence, and reached places as far away as the Indian subcontinent.

Pietra dura would have a profound impact on 16th and 17th Century India. This was the period of the Mughal Empire in India, a period associated with the flourishing of art and architecture. The ruling Mughals admired the newly-discovered technique and commissioned elaborate works in the pieces: the resulting style of pietra dura, or parchin kari was distinctively non-European in its imagery and use.

Indian parchinkari work again was mostly used in architectural rather than decorative settings: one early examples is the famous Tomb of the Emperor Humayun (1508-1556) in Delhi, which was completed in 1569-70. Perhaps the most famous Indian building to feature pietra dura inlay work, however, is the Taj Mahal – perhaps the iconic image of Golden Age Mughal architecture – it is opulently decorated with floral pietra dura inlays on its interior walls, floors and mausolea, and uses rare gemstones such as carnelian, lapis lazuli, turquoise and malachite.

Pietra dura today

Works in pietra dura continue to be made today, though these tend to take the form of reproductions of old designs. Few works can genuinely be considered ‘contemporary’, and even fewer attain the technical sophistication of the Renaissance and Enlightenment-era craftsmen.

There is still, however, a vibrant market for antique pieces made using pietra dura, either in whole or in part. Most of these are 19th Century pieces made in the Renaissance style. Some of the types of pieces you’re most likely to come across when buying antique pietra dura are outlined below.

Tabletops

In the Florentine Renaissance, pietra dura table tops were among the most prized pietra dura pieces, for the most part because they were the largest and were therefore the most technically complicated. Table tops were commonly decorated with intricate patterns of flowers and fruit, completed using the finest stones. The workshops in Florence specialised in making these elaborately inlaid table surfaces for important clients; and still to this day pietra dura table tops are some of the most rare and expensive items available on the market.

Plaques and panels

As well as large table tops, pietra dura workshops found success in making smaller decorative panels for the domestic market. These were intended to be mounted on walls or housed in display cabinets. Common subjects depicted in these panels included human figures, probably inspired by characters from the comedia dell’arte, and so these would include jesters, monks and Italian peasants. Occasionally pietra dura panels would even replicate paintings.

Furniture

Pietra dura would also commonly be used in the Renaissance and afterwards as an inlay technique for large items of furniture such as cabinets. Here the function of the pietra dura decoration was similar to marquetry: a pattern applied into the veneer of the furniture. It was here that one would be most likely to encounter a more three-dimensional form of pietra dura inlay, where stones are applied in a kind of relief. The difference in these cases between pietra dura and hardstone mounting (or even other techniques such as the Japanese inlay method known as shibayama) is not always clear.

Jewellery and caskets

Because pietra dura was associated with the work of lapidary craftsmen, many European jewellers started to incorporate the technique into their work.

Some of the earliest jewellery pieces to be made using pietre dure were cameos and medallions, but the technique was also used to make caskets and jewellery boxes.

Pietra dura jewellery is still hugely popular today, favoured, like pietra dura in general, because of its simplicity of patterning, exoticism of materials, and quality of craftsmanship.

This guide was originally published on the Mayfair Gallery Blog in August 2018.

To view the original version of this article, visit https://www.mayfairgallery.com/blog/pietra-dura-painting-stone