Public art commissions have been around for millennia. Egypt’s Pharaoh Ramesses the Great has been immortalised with four colossal sculptures in the temple at Abu Simbel. Pope Julius II, the Medicis, and the Este and Gonzaga families were prominent Italian Renaissance patrons of the arts. King Francis I of France and King Charles I both appreciated magnificent visual splendour and provided exceptional support. More recent art benefactors have been Peggy Guggenheim, Charles Saatchi, the Broads, Larry Ellison, and the Norton Family, along with many others.

Public art commissions are created for society and must be physically accessible. The artworks are therefore installed and displayed in an easily reachable and welcoming environment. The intention of such a scheme can have various reasons: memorials, celebrating new landmark buildings or specific events, creating a greater sense of identity, and supporting communities to prosper. Overall, the aim is to infuse significance and connect history, present time, and the future. They can be for indoor and outdoor areas, and they vary in size and budget. An assignment requires project management, careful planning, flexibility, and efficient communication between the different stakeholders.

To begin, the commissioner and advisors discuss, draft, and agree on the brief of the project for the announcement. Assignments can be by invitation or through an open call. In both scenarios, guidelines must be provided. After the submission deadline, the pre-selection panel will sift through and evaluate the applications, preparing a longlist for the judges, who in the meantime have familiarised themselves with the details of the competition. Each individual proposition is read and discussed to select or decline a contender. Having a sufficient time frame and consistent process in place is essential. Rejected applicants can request feedback under the Freedom of Information Act when the invitation comes from a public institution.

For the assessment of their designs, specific criteria apply, such as artistic merit, originality, engagement with the community, longevity, maintenance, health & safety, and working within the offered budget. These facts are measured by a point system; the higher a candidate scores, the more likely their chances to be chosen.

The selection process is lengthy. It is a challenging task, deciding why an application is picked, especially when the jury holds opposing views. In an ideal scenario, the judges agree anonymously, opting for the best candidate from the shortlist, but several designs can reach close likings. Hence, the board must once more carefully study and discuss the proposals. The closest contenders are reinvited to present their concepts. Usually, this part of the process enables the panel to narrow down the list of participants, to eventually reach a final decision and announce the winner.

With the support of a legal department or lawyers, a binding contract is drafted, negotiated, and agreed between the artist and commissioner. The document outlines the terms and conditions, which include the details of the involved parties and their responsibilities. The dossier comprises definitions, time frame, insurance, indemnity, fabrication, and installation details. Additional clauses are concerned with health & safety, risk assessments, maintenance, warrants, and financial arrangements. Other legal aspects of the contractual text, such as the ownership, moral rights, copyright, credits, and publicity, as well as delays, disputes, termination, and the de-commission of the artwork are clarified.

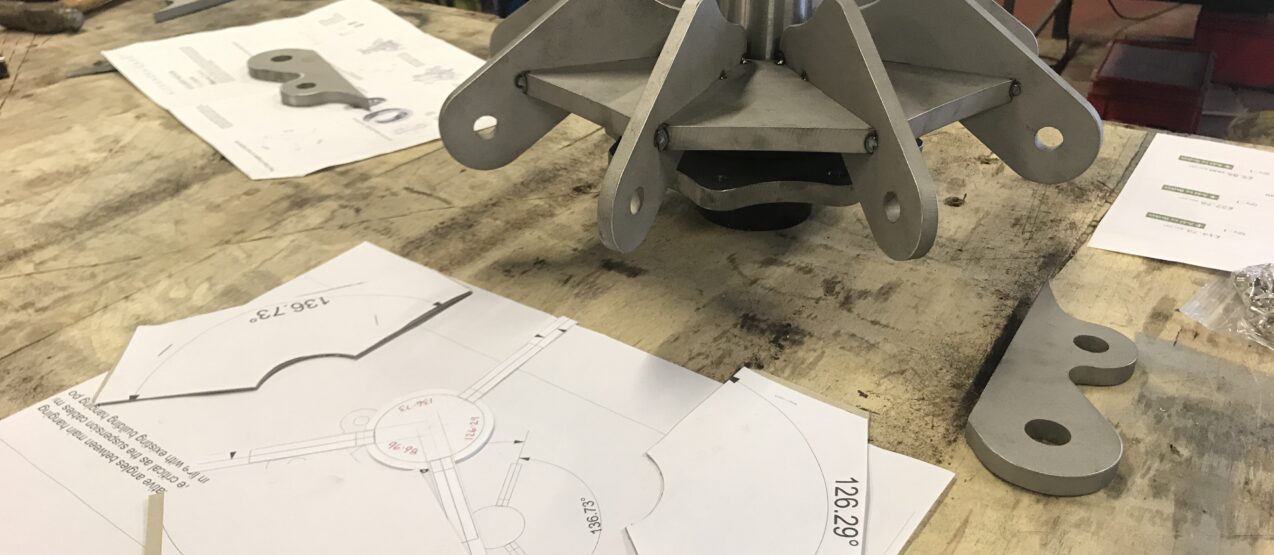

What can go wrong? Materials can be faulty or a breach of health & safety regulations, plus accidents can happen, causing delays and increased administration and costs. Working at heights adds risk factors and must be carefully assessed and overseen. It’s advisable to manage the project in several phases, with planned inspections and signoffs, to ensure the scheme is progressing in the right direction so important milestones are achieved.

Even after the successful delivery of a site-specific installation, relationships can turn sour. For example: the American sculptor Richard Serra created the highly disputed Tilted Arc, commissioned in 1979 by the City of New York for the Federal Plaza, in the financial district. The sculpture immediately attracted adverse responses from individuals working in the location, who perceived the weathered steel wall as an obstacle to their daily routine. After the court hearing in 1985, the sculpture was removed, despite an intense defence from the opposition. For Serra, it implied the destruction of the meaning of the work, and consequently the annihilation of the work itself. The trial involving Tilted Arc is the one of the most ill-famed public controversies in the history of art law. Until now, the sculpture has been kept in a storage facility in Maryland.

Fortunately, most public art commissions do not conclude in this manner. Being engaged in the delivery of such an assignment necessitates excellent communication and project management skills, an understanding of legal, technical, and health & safety requirements, and working closely with an exceptional group of professionals.

This article was written by member Renée Pfister.

Supported by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, Colin Rennie, Cconsult Engineering Design Limited, Blended Management Group, Renée Pfister Art & Gallery Consultancy, London, Architectural Metalworkers Ltd, Ormiston Wire Ltd, Bay Plastics Ltd, Abseil Access, W.H.Scott and Son Engineers Ltd, Constantine Ltd.

Image: Courtesy the artist ©Alexandra Carr and Renée Pfister (text). All rights reserved